The concept of "DNA memory inheritance" has long been a subject of fascination and debate in both scientific circles and popular culture. The idea that memories or experiences of one generation could be biologically passed down to the next through DNA is tantalizing, suggesting a direct link between our ancestors' lives and our own. But how much of this is rooted in fact, and how much is simply wishful thinking or misinterpretation of science?

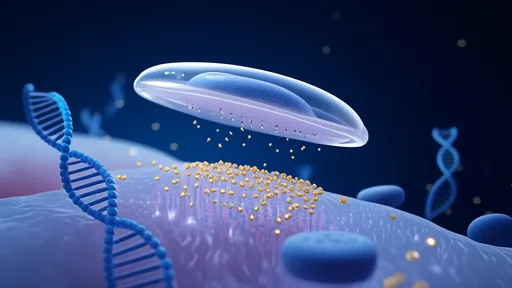

At the heart of this discussion is the field of epigenetics, which studies changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation or histone modification, can be influenced by environmental factors like stress, diet, or trauma. Some studies have suggested that these changes might persist across generations, leading to claims that memories or learned behaviors could be inherited. However, the leap from epigenetic changes to the transfer of specific memories is a vast and largely unsupported one.

One of the most frequently cited examples in support of DNA memory inheritance is the phenomenon of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. For instance, experiments with mice have shown that conditioned fears—such as associating a specific smell with an electric shock—can sometimes be passed to offspring. While intriguing, these studies are often oversimplified in media reports. The mechanisms behind such observations are still poorly understood, and there is no evidence that complex human memories or experiences are transmitted in this way.

Human studies in this area are even more contentious. Some researchers have pointed to correlations between traumatic experiences in one generation and psychological or physiological effects in descendants, such as the children or grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. Yet, correlation does not imply causation, and these studies often fail to account for social, cultural, and environmental factors that could explain the observed patterns. The idea that DNA itself carries detailed memories of past events remains firmly in the realm of speculation.

Another layer of confusion comes from conflating genetic predisposition with memory inheritance. For example, a tendency toward anxiety or resilience might have a genetic component, but this is not the same as inheriting a specific memory of a fearful event. Genes can influence how we respond to our environment, but they do not encode the environment itself. The distinction is crucial but often blurred in discussions of DNA memory.

Critics of the DNA memory inheritance theory argue that the biological mechanisms required for such a process are implausible. Memories are stored in the brain through complex neural networks and synaptic connections, not in the sequence of DNA. While epigenetic changes can affect brain function, there is no known biological pathway by which a detailed memory could be written into DNA and then reconstructed in the brain of a descendant. The scientific consensus is that memories are formed through lived experience, not inherited.

Despite the lack of robust evidence, the idea of DNA memory inheritance persists, fueled in part by its appeal as a narrative. The notion that we carry the emotional or psychological imprints of our ancestors resonates deeply with many people, offering a sense of connection to the past. However, science demands rigorous proof, and in this case, the proof is sorely lacking. While epigenetics has opened exciting new avenues for understanding how environment and genes interact, it has not validated the idea of inherited memories.

In the end, the myth of DNA memory inheritance serves as a reminder of how easily scientific concepts can be misunderstood or exaggerated. While the interplay between genes and environment is undoubtedly complex, we must be cautious not to overinterpret preliminary findings. The true story of how our past shapes us—biologically and psychologically—is still being written, and it is far more nuanced than any simple tale of inherited memory.

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025